Science Seen Physicist and Time One author Colin Gillespie helps you understand your world.

What does that Black Hole image tell us? Much more (and also less) than you may think.

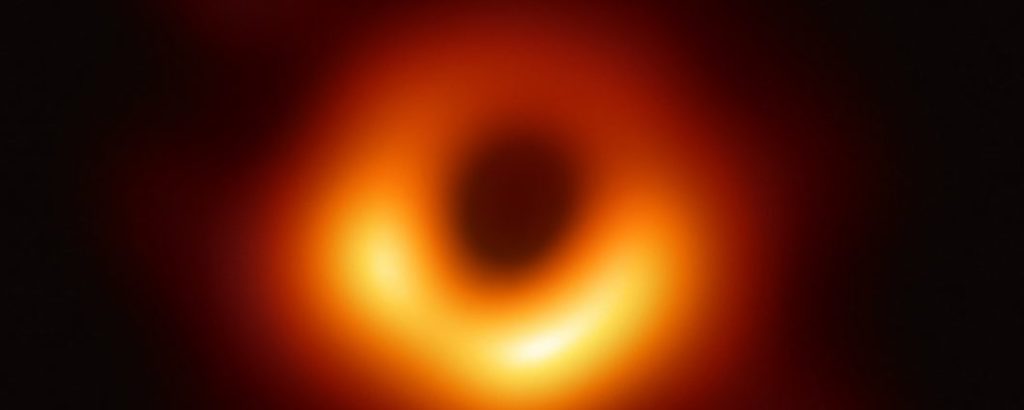

We’ve all seen that vast black hole. Its six billion solar masses are so dense no light can escape. It is so far away light from hot gas falling in takes 55 million years to reach us.

Well actually, we’ve seen an image. Now that we’ve seen it, what do we know now we didn’t know before?

Some say: Now we know black holes are real. For example, one researcher claimed the image will turn black holes from a mythical object into “something concrete we can study.” As we will see, they are wrong.

Let’s take a closer look. The Event Horizon Telescope that found it sees no light. It picks up radio signals. It is not a single instrument; it’s a consortium of eight telescopes around the world. They must be that far apart to resolve the image at that distance; it’s like looking from your front door for a silver dollar Neil Armstrong dropped on the Moon. And the black hole itself is hidden behind a frontier (called the event horizon) from beyond which not even light can emerge.

Let’s take a closer look. The Event Horizon Telescope that found it sees no light. It picks up radio signals. It is not a single instrument; it’s a consortium of eight telescopes around the world. They must be that far apart to resolve the image at that distance; it’s like looking from your front door for a silver dollar Neil Armstrong dropped on the Moon. And the black hole itself is hidden behind a frontier (called the event horizon) from beyond which not even light can emerge.

Two hundred astronomers, mathematicians, physicists and engineers spent two years processing the signals. Their work hinged on a computer algorithm computer-science student Katie Bouman developed to make sense of them. In effect it asks, “What could be out there to send us a set of signals like this?”

Two hundred astronomers, mathematicians, physicists and engineers spent two years processing the signals. Their work hinged on a computer algorithm computer-science student Katie Bouman developed to make sense of them. In effect it asks, “What could be out there to send us a set of signals like this?”

So, that image is a computer message saying: “Trust me; this is what you’d see with a ten-thousand-mile-wide eye if you could see it.” And the researchers explain why we should indeed trust it.

But amazing though this image is, the reality of what we see is nothing new: It is what science expected.

Far from mythical, black holes are already well studied. For example, we’ve seen the universe shudder when two collide.

We knew this one was there; we knew it was 55 million light years away; and we knew it was big. That’s why those telescopes tried looking at it. Scientists hadn’t seen the black hole but they had seen what it was doing. They still haven’t seen the black hole (and they never will). What they’ve seen now is a bit more of what it’s doing (or, rather, what it was doing 55 million years ago).

Fact is, science already knew black holes were real and—sexy though it surely is—that image tells us nothing more about this.

But the image’s reception by the scientific community is a harbinger of bigger things. It is a sign that science (and physics in especial) is a-changing.

For more than a hundred years science used observation and prediction to beat two paths beyond what we see. One observed ever larger objects in the universe. The other observed ever smaller particles of matter.

Now observing has hit a frontier in both directions. In light emitted right after the Big Bang we can observe almost 13.8 billion light years away and no further; but the universe is much bigger. And with giant accelerators like the Large Hadron Collider we can observe sub-subatomic particles; but the basic bits of space and matter are far smaller than the smallest of them.

Is this the end of mankind’s long progress in pushing the boundaries of basic science? Maybe not, if science can adapt its observation-and-prediction methodology. Instead of prediction, it must pursue explanation. But—and this is a big “but” for physicists—by its nature, explanation means turning once again to reality.

Einstein did exactly that, even with that most difficult aspect of reality: space—which generations of physicists have dismissed as “nothing”. By 1920, he was saying, ‘It is indeed an exacting requirement to have to ascribe physical reality to space in general, and especially to empty space.’

If space is (as he concluded) something, it is made of pieces (flecks) far smaller than science can observe. They are hidden forever beyond that frontier.

Yet, just as the Event Horizon Telescope’s computer can explain those world-wide radio signals with an image of a black hole, physics is increasingly looking to explain a raft of real-world information with a detailed image of a fleck of space.

Physics may be getting real again. That’s really exciting!

Image credits:

EHT Collaboration; https://www.eso.org/public/images/eso1907a/

EHT Collaboration; eventhorizontelescope.org

MIT

No comments yet.