Science Seen Physicist and Time One author Colin Gillespie helps you understand your world.

With a new way to measure space we may learn why it is expanding.

These are exciting times. Every few months astronomy surprises us with insights into ancient secrets.

New telescopes are scanning galaxies throughout the visible universe. Most galaxies are mind-bogglingly far away. Exactly how far has long been a fundamental issue. But we just got a whole new way to measure it.

Today the universe is much bigger than it was in this Planck-satellite image from almost fourteen billion years ago, a few hundred thousand years after it began. It’s not that the universe now has more matter: It has about a thousand-fold more space.

In 1908 American astronomer Henrietta Leavitt devised a method for measuring vast expanses of space. Called a standard candle, it used a kind of variable star. Each star’s absolute brightness is related to its period of variation, which she could measure and use to calculate its distance.

Leavitt extended our direct grasp of distance from one hundred light years to ten million, far beyond our own galaxy. She paved the way for Edwin Hubble’s famous measurements that revealed an expanding universe.

One might say Leavitt launched the practice and then Einstein launched the theory of cosmology. She is (no surprise) a mostly unsung hero.

Other kinds of standard candles now extend measurements of distance to the farthest reaches of the universe—but have uncertainties of 25% or more. This lack of precision hampers understanding.

A new kind of astronomy offers a much more precise kind of standard candle. Its reach is at least three hundred million light years.

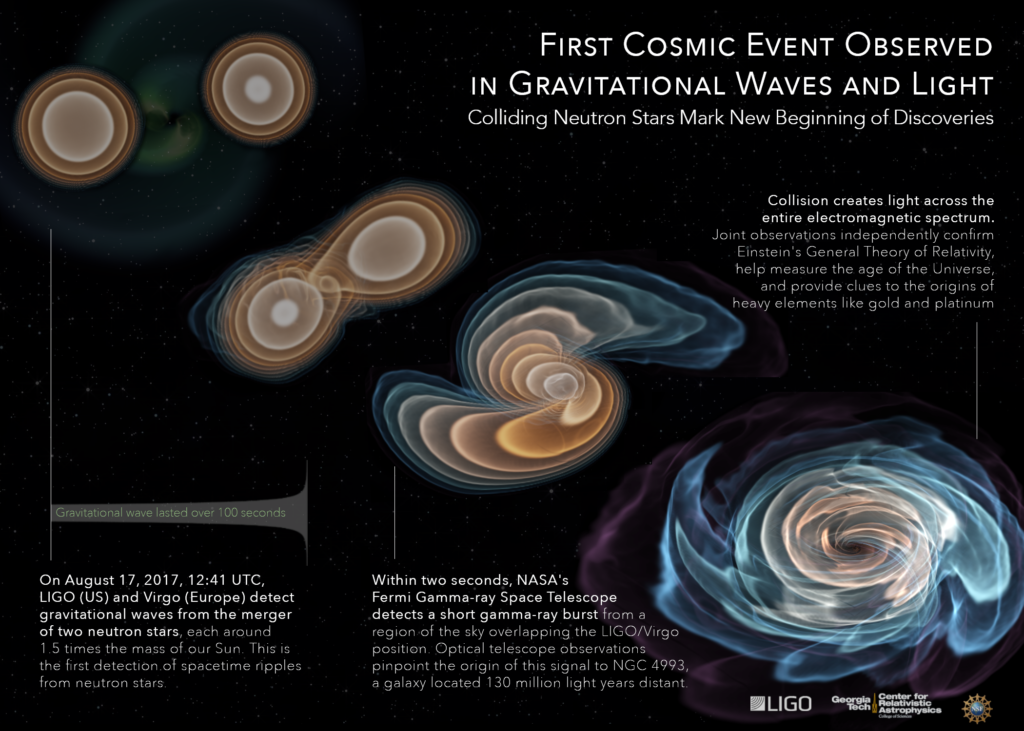

Einstein and Leavitt would both have been delighted by how it arrived. More than a hundred million years ago two dead stars made mostly of neutrons—each with more mass than our Sun and the diameter of Nashville, each spinning maybe twenty times a second while in close frenzied orbit round the other—kissed and instantly smashed. In the next minute the smash released more energy than a billion galaxies of a hundred billion stars each.

Momentarily this event put out maybe one percent of the total energy of all the stars in the visible universe. Six months ago, waves of that energy arrived at Earth.

This collision was not an unusual event. What was unusual was the world’s astronomers saw it, because they knew where and when to watch. They had rushed to their telescopes because detection of gravitational waves from the final frenzy—ripples distorting the fabric of space itself——gave notice of the impending collision and showed where it could be seen in the sky.

Astronomers can learn a lot from watching a neutron star collision with measurements from many different instruments. For example, they saw signs it set off an exotic nuclear reaction that transmuted iron into gold—enough for a solid planet-sized nugget.

With this same event astronomy struck gold of a different kind: These measurements confirm math (based on Einstein’s theory) that predicted a wide range of signals expected from a two-neutron-star collision. Almost unnoticed in the torrent of discoveries is that built into the math is a direct and precise measure of its distance from us.

This may prove to be the most significant discovery of them all. For starters it provides a better calibration for the longest-distance standard candles. And it is a standard candle in its own right, though maybe a relatively rare one.

Space has been expanding since the dawn of time. This may be our best clue to how the universe began.

Precisely measuring vast distances allows us to better study not only how fast space is expanding—currently a controversial question—but also how the speed of expansion has been increasing.

And to ask that most curious of questions: Why?

Image credits:

European Space Agency; http://www.esa.int/spaceinimages/Images/2013/03/Planck_CMB

LIGO Scientific Collaboration; https://www.ligo.org/detections/GW170817.php

Thank you, Sister. Happy, safe sailing.

Amazing way of describing a subject fraught with complexity one can understand and relate to it.